A Disturbing Entrance

Palm Sunday of the Passion of the Lord. Fr Colin Carr preaches on three things that distinguish Matthew’s account of Holy Week.

A person gets remembered in all sorts of different ways: no two people will have exactly the same memories, but their different memories will build up a whole picture which gets more interesting the more it is added to.

Many different people wrote about Jesus in the decades after his death. Four accounts of his life and teaching, his death and resurrection, are found in the Christian scriptures. They’re interestingly similar and they’re interestingly different.

I want to look at three things which Matthew’s gospel says about Jesus’ last days — things which the other accounts don’t mention.

The first is that Jesus came riding into Jerusalem not on one donkey but on two — a donkey and a colt. The disciples laid their cloaks on them; Jesus sat on them. And the result was that the whole city was in turmoil. Matthew stresses that this is a fulfilment of an ancient prophecy that Zion’s king would come riding

on a donkey, and on a colt, the foal of a beast of burden.

These days the scholars insist that Matthew was reading the prophecy too literally, that the prophet had only referred to one animal: it was a donkey, and, to be precise, a colt; just as we might say:

She’s a tennis player, and a very good tennis player too.

Maybe the prophet did originally have only one animal in mind; but Matthew’s gospel was written by someone who reflected deeply on the way Jesus made the old prophecies come alive, and who noted that when Jesus did fulfil an ancient prophecy, he caused a stir.

Perhaps he wanted to stress how very humble Jesus’ view of kingship was — ludicrously humble, we might say. Perhaps the parent donkey and the foal represented for him the old and the new which Jesus held together in his teaching and his life; he wasn’t averse to allegories.

But for Matthew, above all Jesus was fulfilling what had been promised by God’s seers in the past. He was responding to a destiny and a vocation which might have uncomfortable consequences and might cause a stir, but so be it. The promise to Abraham was accompanied by a command to go precariously into the unknown; it was being fulfilled by the humble king who rode precariously towards his deadly throne.

A second incident which only Matthew records is the message which Pilate’s wife sent to Pilate as he was sitting on his judgement seat; he was trying, rather feebly, to do justice. His wife tried to influence him to leave well alone — to dismiss the case: she had been suffering all day because of a dream about this just man, Jesus.

Pilate knew that the motives of Jesus’ accusers were not good; his wife insisted Jesus was innocent; but Pilate was prevailed on by the loud voices of the crowd, and he did what was expedient rather than what was just. The yells of the crowd were more persuasive than the rather vague voice of a dreamer. Dreams don’t rate highly as persuaders in a world of harsh political realities.

The woman who dreamed, and was upset by her dream, didn’t seem like a strong advocate for the innocence of Jesus. But it is only people like her who can recognise Jesus for what he is. He appeals to more than just our calculating common sense: he is found by those who are open to their imagination, who are able to be disturbed by him.

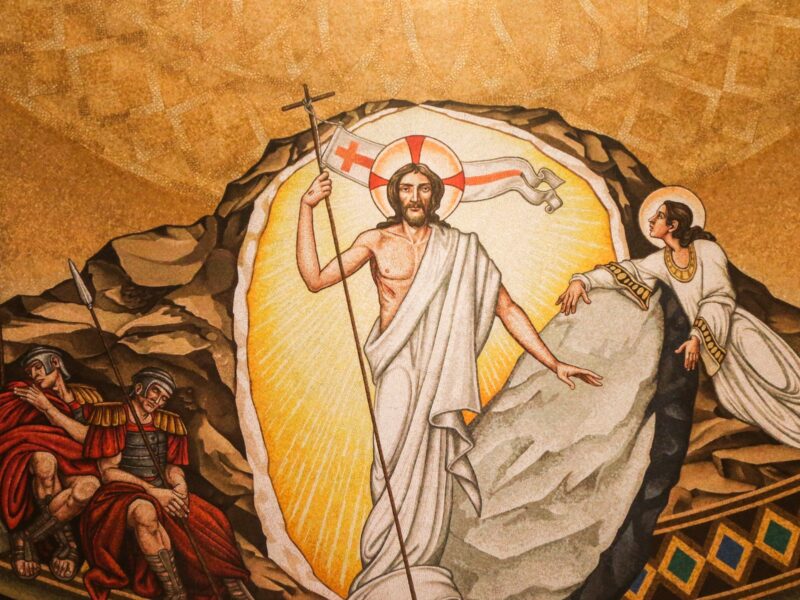

The third special contribution of Matthew is the earthquake, the splitting of the rocks and the raising of the saints, who visited the Holy City after Jesus’ resurrection. (Don’t ask me what they did on Saturday – it’s puzzling enough as it is.)

The earth was disturbed — the same word as is used for the disturbance Jesus brought to the city when he rode in on two donkeys. Jesus fulfilled his destiny, and caused a disturbance. Again.

Jesus the disturber came into the city, and the disturbance turned the city against him; he disturbed Pilate’s wife through a dream, and she allowed herself to be convinced of his innocence; his death disturbed the rocks which held the dead, and the dead came to life.

Jesus will always be the disturber; we choose whether his troublesome approach will turn us away from him to comfortable expediency, or teach us the truth and bring us life.